“What fools these dictators are” – Neville Chamberlain

I did this to inform myself before tutoring a British A Level History candidate who has to write 3000 word piece to answer this question: “What is your view about the appropriateness of appeasement as the basis of British foreign policy“. I had judged that the Rhineland episode was a perfect example of Appeasement in action. Only after a fortnight’s delay did the candidate add that the question confined itself to the period 1937-9, which makes this piece less helpful, but by no means useless. The whole point of History is that it hangs over the present and influences it. It is sad that past computer crashes appear to have deprived me of detailed studies of the Spanish Civil War and the Phoney War. I have also used only one font (Garamond) to make insertion in the website simpler, so corroborated facts are simply in the Black Bold version of that font.

Contents

Background to the Rhineland Episode

International Relations after Versailles

Historiography: Continentalists

2: destroy the Treaty of Versailles

4: to destroy the Locarno Pact

6: to destroy the Communist USSR

Germany leaves the Disarmament Conference 23rd October 1933

Anglo-German Naval Pact June 1935

German-Polish Pact 28th January 1934

Repudiation of Versailles March 1935

Operation Winter Exercise March 7th

Responses to the German re-occupation

French Foreign Policy: Laval 1934-6

Austria, Czechoslovakia and Poland

Was Appeasement reprehensible?

Appendix 1 – Bibliographical Notes

Definition of Appeasement

Appeasement is (1,3) the name for the foreign policy of the Western European countries of Britain and France towards Germany. (13) It refers to compromising with acts of aggression, sacrificing some nations in order to protect the world from war. (11) [OR] a foreign (1,3) or any (5) policy of pacifying [OR] giving into the demands of (13) an aggrieved nation through negotiation (1,3) an aggressive country in the hopes that the aggression could be contained (13) [OR] they would be satiated (3) and avoid war. (1,3) [OR] the fall-back position when it was impossible to make a major decision: (12) Allowing direct violation of the Treaty of Versailles without doing anything to stop Hitler was appeasing him. (17) Nations like Britain and France were unprepared for war and so they did not want to create greater conflicts with Germany. (17)

When was Appeasement?

Appeasement refers to the foreign policy of England and France (18) in the years after World War I but before World War II (13,18) in 1919 after the Treaty of Versailles. (18) It predates Chamberlain’s premiership. (18) [OR] in the years prior to WWII. (5,18) between 1937 and 1939, (5)

Background to the Rhineland Episode

World War I finished with Russia paralysed by revolution, Germany defeated and France and Britain bankrupt. (8a)

Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles, signed in July 1919–eight months after the guns fell silent in World War I–called for stiff war reparation payments and other punishing peace terms for defeated Germany. (7) Having been forced to sign the treaty, the German delegation to the peace conference indicated its attitude by breaking the ceremonial pen. (7) As dictated by the Treaty of Versailles, (7,17) Germany’s military forces were reduced to insignificance (7) and the Rhineland was demilitarized. (7,10) Woodrow Wilson intended all problems to be settled by negotiations at the League of Nations, but he was soon dead and the US became isolationist. (8a) All sides tried to resume normal business. (8a)

International Relations after Versailles

The British refused to allow the French to enforce reparations on the Germans, and the Americans finally agreed to pay themselves back via the Dawes and Young Plans. (8a) During the 1920s Britain had control. (18) OR Both British and French struggled to control their empires. (8a) The French official ruling Indo-China was bombed several times, and the British massacred a crowd of Indians at Amritsar. (8a) The Germans and the Russians, both refused a role in the peace settlement, made an alliance which allowed German troops to be trained in Russia in return for Russian supplies. (8a)

Locarno

The British and French had no confidence in the League controlling Germany. (8a) During the 1920s pacts and treaties of assistance and friendships provided encouragement for the French to engage in disarmament and step down from aggressive policies against the Germans. (9) The most important of these was the Locarno Pact, (7,9) signed in 1925, (7) [OR] 1925 (25) at the conclusion of a European peace conference held in Switzerland. (7) It ignored the League (8a) and reaffirmed the national boundaries decided by the Treaty of Versailles (7) [OR] ‘Germany’s western borders’ (8a) and approved Germany’s entry into the League of Nations. (7,8a) The so-called “spirit of Locarno” symbolized (7) hopes for an era of European peace and goodwill. (7,9) Sir Austen Chamberlain called the Locarno Pact as “the real dividing line between the years of war and the years of peace.” (25) The “Locarno Spirit” from 1924 caused the search for security to lose its imperative character under the influence of growing confidence. (25) The Germans had revealed their eastern wish list at Brest-Litovsk, and had it snatched from them at Versailles. (8a) Keen observers now noted the Locarno Treaty’s invitation to the Germans to expand east, but most people thought things were settling down nicely. (8a)

Kellogg Pact

The Kellogg-Briand Pact, signed in 1928 by French foreign minister Aristide Briand and American Secretary of State Frank Kellogg, (9) [OR] ‘by all countries’ (8a) provided ‘for the renunciation of war as an instrument of national policy’. (9) By 1930 (7) [OR] in 1928, 5 years earlier than scheduled in the Treaty of Versailles (9) German Foreign Minister Gustav Stresemann had negotiated (7) the removal of the last Allied troops in the demilitarized Rhineland. (7,9) In 1930 the last French troops left occupied Germany. (6) A challenge to peace came from dictators, first Benito Mussolini of Italy, then (3,6) in January 1933 (4) Adolf Hitler of (3,6) a much more powerful Nazi Germany. (3) When the Nazis took over in Germany and Italy’s Mussolini announced his intention to annex territory (6) the League of Nations proved disappointing to its supporters; it was unable to resolve any of the threats posed by the dictators. (3)

The Slump

The Slump changed things. (8a) Communist Russia seemed to have avoided it, so Communism seemed a good idea to many, which provoked right wing ‘fascist’ opposition to it, particularly in Italy, Germany, Spain and Portugal. (8a) Many governments were lacking money due to the Great Depression. (11)

Manchuria, 1931

Japan intended to gain influence, territory and power in mainland Asia. (11) [OR] The Japanese needed raw materials, and (8a) was unhappy with what it had received from the peace process in WWI (8a) in 1931 Japan invaded Manchuria in order to expand its Empire. (11) It took Manchuria in spite of the League’s protests, leaving the League in the process. (8a) The world did nothing, as it was the start of the Great Depression and few nations had money to save poor Manchuria. (11) Every time there was some sort of aggression by a nation like Italy, Germany or Japan the world largely ignored it or tried to negotiate with them to take what they had gained and stop. (11)

Hitler

Foreign Policy Aims

Historiography: Globalists

In the 1960s Gunter Moltman and Andreas Hillgruber who, in their respective works, claim that it was Hitler’s dream to create ‘Eutopia’ and eventually challenge the United States. (24) This thesis puts these two historians in the ‘Globalists’ category, with opposition labelled ‘Continentalists’. (24) Evidence for these claims comes from Germany’s preparation for war in the years 1933–39 with increased interest in naval building, and Hitler’s decision to declare war on the U.S. after the attack on Pearl Harbor, which shows Hitler’s determination. (24) The Globalists use this as an argument for how Hitler’s ideology was shaped; i.e. the US could only be defeated if Germany conquered Europe and allied with Britain. (24) It is said with general agreement that this viewpoint expressed by Hitler was written with the mindset that the USA was of little interest to Germany, and did not pose a threat to her existence. (24) However, noted through speeches and recorded conversations, after 1930, Hitler viewed the United States as a “mongrel state”, incapable of unleashing war and competing economically with Germany due the extreme effects of the Great Depression. (24) Even in the late 1930s, as Continentalists argue against world conquest, Hitler seems to still disregard the US’s power in the world, and believes that only through German-American citizens can the USA revive and prosper. (24) This may shed light as to why Hitler made the decision to declare war on the United States after Pearl Harbor, and continued to focus on European expansion in the late 1930s. (24) However, while Hildebrand believes Hitler had a carefully premeditated Stufenplan (step-by-step) for Lebensraum, Hillgruber claims he intended intercontinental conquest afterwards. (24) Likewise, Noakes and Pridham believe that taking Mein Kampf and the Zweites Buch together, Hitler had a five-stage plan; rearmament and Rhineland re-militarisation, Austria, Czechoslovakia and Poland to become German satellites, defeat France or neutralise her through a British alliance, Lebensraum in Russia and finally world domination. (24) Goda agrees, believing that his ultimate aim was the defeat and overthrow of the United States, against whose threat he would guarantee the British Empire in return for a free hand to pursue Lebensraum in the East. (24) Hitler had long term plans for French North Africa and in 1941 begun to prepare a base for a transatlantic attack on the United States. (24) David Cameron Watt, who in 1990 believed that Hitler had no long terms plans, now agrees with Goda and believes that Hitler refused to make concessions to Spanish and Italian leaders Francisco Franco and Benito Mussolini in order to conciliate a defeated France so that such preparations could proceed. (24) Jochen Thies There are other arguments for the case of the Globalists; Jochen Thies has been noted to say that plans for world domination can be seen in Hitler’s ideology of displaying power. (24) The creation of magnificent buildings and the use of propaganda to demonstrate German strength, along with the message to create a Reich to last a thousand years, clearly show Hitler’s aspirations for the future. (24) Although this seems a weak argument to make; clearly these messages are a result of Nazi Ideology intent on creating followers and boosting morale, what stems from this is the idea of ‘global character’ in reference to war. (24) There is no doubt that Hitler dreamed about the future of his Homeland, and in preparations for war, must have thought about the consequences of victory over the USSR. (24) His struggle, as he would reference in his book Mein Kampf, would and eventually did take on a global character, as he found his country fighting wars on many fronts across the world. (24) The Globalist mindset for Hitler’s foreign policy can be supported by the spiraling events of World War II, along with his second book and the debatable meaning of Lebensraum; although the Continentalists can use Lebensraum as evidence to counter. (24)

Historiography: Continentalists

Fritz Fischer Fritz Fischer, a continentalist historian who has done extensive work on German history, claims in his book From Kaiserreich to Third Reich: Elements of Continuity in German History, 1871-1945 that foreign policy was just a continuous trend from Otto von Bismarck’s imperialistic policies; that Hitler wanted an empire to protect German interests at a time of economic instability and pressure from competing global empires. (24) Other views Martin Broszat Martin Broszat, a functionalist historian, has been noted many times to point towards an ideological foreign policy fuelled by antisemitism, anti-Communism and Lebensraum. (24) He says that Hitler acted towards these three ideals to inspire popularity in his regime and to carry on the amazing transformation he ignited upon coming to power. (24) In relation to foreign policy, this meant the destruction of the Treaty of Versailles and the reuniting of German territories lost after World War I, along with the eradication of Jews and communists around the world. (24) He provides evidence with preparations made in 1938 to take land in the East of Europe, which fits in with the ideology of colonization, economic independency, and the creation of the Third Reich. (24) Broszat offers a Continentalist case in declaring that Hitler was still dreaming of Eutopia when he did not include Poland in his plans before 1939, and focused upon Czechoslovakia and Austria instead; easily attainable territories. (24) Broszat argues against world conquest in this respect, and notes that the escalating ideological radicalism of the Nazi’s anti-Semitic views prevented them from being able to launch a truly serious attempt to take over the world. (24) Germany found itself unwillingly in a world war, not a European one. (24)

Historiography: A.J.P.Taylor

In 1961, A.J.P.Taylor produced a book entitled The Origins of the Second World War, which paints a completely different picture of how Nazi foreign policy was shaped and executed. (24) Taylor’s thesis was that Hitler was not the demoniacal figure of popular imagination but in foreign affairs a normal German leader, and compared the foreign policy of the Weimar Republic to that of Hitler, i.e., wanting the destruction of the Treaty of Versailles and wanting her former territories back but by peaceful means, not aggressive. (24) His argument was that Hitler wished to make Germany the strongest power in Europe but he did not want or plan war. (24) The outbreak of war in 1939 was an unfortunate accident caused by mistakes on everyone’s part. (24) In addition, Taylor portrayed Hitler as a grasping opportunist with no beliefs other than the pursuit of power and to rid himself of the Jewish question. (24) He argued that Hitler did not possess any sort of long-term plan and his foreign policy was one of drift and seizing chances as they offered themselves. (24) He assigns blame on the harsh restrictions of Versailles, which created animosity amongst Germans, and when Hitler preached of a greater Germany, the public believed in his words and was ready to accept. (24) However, the idea put forward that he was a gifted opportunist that, although Taylor completely rules out long term planning, Hitler was shrewd enough to seize upon when presented has a lot of evidence. (24) For example, he used the appeasement policies of Britain and France to deliberately defy them in March 1935 when he announced conscription into the army and creation of the Luftwaffe. (24) He gambled upon the Austrian government to not oppose him when he invaded Vienna in March 1938 after realizing Britain and France would never intervene. (24) He used the opportunity of the September 1938 Munich conference to make Britain and France accept his demands for Lebensraum in Czechoslovakia. (24) He used the breakdown in relations between Britain-France and the Soviet Union to sign the Nazi-Soviet non-aggression pact to solidify his future actions against Poland and the Netherlands-Belgium. (24) Taylor’s point on this debate sparked uproar and widespread rebuttal, but the whole argument on the nature of Nazi foreign policy was created from his work. (24)

Aims

Just four years after the removal of the Allied forces in the Rhineland, Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party seized full power in Germany, promising vengeance against the Allied nations that had forced the Treaty of Versailles on the German people. (7) [OR] declaring that their main enemies were Communists and the Soviet Union, along with the Jews. (4) He had already set out his ideas in a book called Mein Kampf (My Struggle) (20,24) that he had written in prison in 1924. (20) and added to this in his ‘Zweites Buch’. (24) His Foreign Policy had four (15) [OR] three (16) [OR] six (HN from list after book 16) (15) [OR] five (after book 19) aims. (20) These amounted to (2,4) a revisionist (2) policy aimed at overcoming the (2,7) humiliating (14) restrictions imposed on Germany by the Treaty of Versailles (2,7)

1: Make Germany Great Again

When Hitler came to power he was determined to make Germany a great power again (17,20) to this end he intended to stir up nationalistic feelings of the Germans to gain revenge for Germany being humiliated in World War I; Hitler promised that he would bring back the glory and redemption that Germany had lost. (17) To achieve his foreign aims he needed to crush internal opposition, which he did using the SA, and the Gestapo secret police, and passing the Enabling Act, and gaining control of the army after death of Hindenburg. (21) He needed to win over the German people to his policies through education, censorship and propaganda. (21) In particular he needed to prepare German youth for future war. (21) His policies would involve re-arming Germany (15,16) removing limitations on German armaments. (14) He planned to overcome the depression (17,21) by a new economic plan to satisfy the middle and working class. (21) This would lay the foundations for a stronger Germany. (21) His ‘Four Year Plan’ (implemented by Schacht 1936 – 1940) would revive the German economy by limiting imports, as Germany depended on imports for 1/3 of their raw materials. (21) It would strengthen the currency and increase government spending. (21) It proposed to reduce unemployment by public works projects, by filling the jobs of Jews and political opponents with unemployed people (21) and by conscription into the army. (17,21) This plan prepared for a short term blitzkrieg rather than bettering people: not much was produced in the way of consumer goods, and not everyone received their promised Volkswagen. (21) He would strengthen Germany’s borders (16) by recovering its lost lands (14,15) such as the demilitarized Rhineland (14,17) [OR] He did not attempt to recover the lost colonies outside Europe. (4) If he achieved the foregoing, Germany would dominate Europe. (20) By seizing the diplomatic initiative from Britain and France, (2) he would give Germany economic and political domination across central Europe. (4,20) He should in the end rule all Europe because otherwise it would fall apart as a nation, (21) and by doing so he would re-establish Germany’s position in world affairs. (14)

2: destroy the Treaty of Versailles

To make Germany Great he would have to destroy (2,7) [OR] revise (21) the Treaty of Versailles. (2,7) He said that the chains of that treaty needed to ‘fall with a loud clang’. (14) The treaty had reduced the army to 100,000 men, and the navy to six warships of over 10,000 tonnes. (21) No submarines or air force were permitted. (21) Hitler felt the Treaty was unfair and most Germans supported this view (20) and the modern historian John Clare says that ‘there can be some sympathy for them’ because ‘they had been the only ones to disarm under the Treaty of Versailles’. (21) Hitler’s aims could not be obtained without armed forces so he worked to make them suitable for war. (21) Hitler had to rearm to be able to succeed. (21) He would weaken the international system set up at Versailles by rearming, at first secretly, and then openly. (21) He would withdraw from the Geneva Disarmament Conference and League of Nations. (21) He wanted to recover the Sudetenland because it had coal and copper mines, power stations, good farming land, the Skoda arms works, the biggest in Europe, and frontier protection, from the Bohemian Alps and its chain of fortresses. (21)

3: Create a Greater Germany

An aspect of this was to bring all German-speaking people everywhere under German control; (15,16) After World War One there were Germans living in (20,21) many countries in Europe e.g. Austria, (20,21) the Sudetenland in (21) Czechoslovakia, (20,21) Poland. (20) Hitler hoped that by uniting them together in one country he would create a powerful Germany or Grossdeutschland. (20,21)

4: to destroy the Locarno Pact

To destroy the Locarno Pact. (17)

5: Lebensraum

The 4-Year economic plan could only provide for a short war; (21) so Hitler was an expansionist like Napoleon Bonaparte. (17) He wanted to expand eastwards to gain Lebensraum (‘living space’) for the German people. (14,15) Hitler believed that for Germany’s growing population to be independent (21) this space (14,20) as far as the Caucasus and Iran (21) needed to be acquired (14,20) [OR] it did need to be acquired (17) in the east, at the expense of the Soviets, (14,20) and Poland (20) so as to secure for Germany the Ukrainian “breadbasket”, opening up vast territories for German colonization. (14) [OR] Hitler reoccupying the Rhineland is an example of expansionism. (17) Beyond the Rhineland he also aimed at acquiring Flanders ( Belgium ) and Holland. (21) He needed Sweden to give Germany access to the open sea sufficient to become a colonial power. (21) Germany took the Rhineland but started expanding East later on, (17) finding justification for such conquests in his notions of German racial superiority over the Slavic (14,21) and Jewish (21) peoples who inhabited the lands he coveted. (14,21)

6: to destroy the Communist USSR

To destroy the Communist USSR: (14,15) Hitler saw the Bolsheviks who now controlled the Soviet Union as the vanguard of the world Jewish conspiracy, (14) He would have to defeat Russia to get hold of the Ukraine. (14)

There were three stages to his foreign policy. (16) A moderate policy up to 1935. (16) Increased activity between 1935 and 1937. (16) A more confident foreign policy after 1937, certain that there would be little opposition to his plans. (16) From 1933–1938, Konstantin von Neurath, a conservative career diplomat, served as German foreign minister. (2) Policy was not down to him, as Hitler kept tight control over foreign affairs, formulating himself both the strategy and the tactics calculated to achieve his goals. (14) Control of this territory was to become the foundation for Germany’s economic and military domination of Europe and eventually, perhaps, of the world. (14) Hitler’s diplomatic strategy in the 1930s was to make seemingly reasonable demands, (4) threatening war if they were not met. (4,20) He began to carry out aggression (4,13) towards other nation-states in Europe and (13) carried out actions that went against the general terms of the Treaty of Versailles (13,15) to see if anybody would challenge him. (15) [OR] He realised that his potential foes, France and Britain, were reluctant to go to war and were prepared to compromise to avoid a repeat of World War One. (20) A J P Taylor argued that Hitler did not deliberately set out for a destructive war: Hitler was an opportunist and made gains in his foreign policy by direct action and audacity. (16) Hugh Trevor-Roper, on the other hand, argued that Hitler had a long term plan – a programme of colonisation of Eastern Europe and a war of conquest in the West. (16) This Stufenplan, step-by-step policy, led to war. (16) Probably the most convincing argument is that Hitler had consistency of aims, (16) but was also an opportunist that was flexible in his strategy. (16,20)

Withdrawal from the League

Germany withdrew from the League of Nations; (2,4) on October 14th (Google) 1933. (4,20)

Germany leaves the Disarmament Conference 23rd October 1933

Nine days after leaving the League, (Google) Hitler left the disarmament conference, (15,20) claiming that the Allies had not disarmed (20) and were not prepared to disarm. (15) He claimed that he wanted peace and to disarm fully with his neighbours. (15) 21 disagrees: “everything was good internationally up to 1935. (21) The Disarmament Conference ceased to function after January 1934. Britain ironically drew the conclusion that disarmament had become more important than ever. (25) The affiliation of the British Government with the German became so close that the anti-Semitic movements and eugenic craze in Nazi Germany were, by official British authorities, treated as unfounded, exaggerated, or were simply ignored. (25) The British press instead concentrated on the suppression by Stalin and the secretive system of the Soviet Union. (25) Although Germany after Hitler’s control had boosted up its armaments, the British administration responded with further disarmament, and Stanley Baldwin, then prime minister, regarding a possible German invasion, “did not consider such an attack likely”. (25)

Rearmament

No such domination or expansion as Hitler intended was possible without war, of course, and Hitler did not shrink from its implications. (14) Using the pretext that the other powers had not disarmed, (15,20) he rebuilt the military and blazingly showed it to the world. (11,14) In a secret meeting (21) he ordered Germany into (11,16) rapid (2,16) rearmament (2,4) in March (14,20) 1935. (4,14) [OR] 1933. (11,21) [OR] His rearming of Germany, begun in secret in 1933, was made public in 1935. (14,21) after the Saar plebiscite result (21) [OR] In 1933 he intensified the programme of secret rearmament. (20) He started building planes, tanks, submarines and weapons. (11) In 1935, (16) Hitler said that Germany was going to expand her navy. (20) He announced the creation of an air force (14,16) (the Luftwaffe) (20,21) which would have 1000 aircraft with secretly trained pilots, plus barracks, airfields and fortifications. (21) He announced that Germany considered itself no longer bound by Part V of the Treaty of Versailles (25) The reintroduction of general military (14) conscription, (14,15) which was banned by (15,20) Part V of (25) the Treaty of Versailles (15,20) to provide the manpower for 36 new divisions in the army. (14,20) All young men spent six months in the RAD and then (16) they were conscripted into the army. (16,25) The German army would be enlarged from 100,000 to 300,000 (21) [OR] 600,000 [OR] 500,000 (21) men (25) The British Government immediately protested to Berlin against this independent action which rendered an agreement well-nigh impossible. (25) Nothing could alter the fact, however, that Germany had rebelled against the imposition of the Treaty. (25) By 1939, 1.4 million men were in the army, so they were not counted as unemployed. (16) This created jobs in the armaments industry pushing the idea of ‘guns before butter’. (16) These measures were very popular in Germany. (20)

Anglo-German Naval Pact June 1935

A factor that helped Hitler was the attitude of the English. (20) Protecting their own interests, (20,25) and even though Germany was forbidden to rearm, (15) Britain agreed a (14,15) separate (25) deal with Hitler (14,15) in June of that same year, (14,21) that allowed a German naval build-up of up to 35 percent of Britain’s (14,15) surface naval strength (14,25) and up to 45 percent of its tonnage in (14) [OR] an equal tonnage of (21) submarines (14,21) [OR] No limit was placed on the number of submarines that Germany could develop. (20) Britain let this happen because it was to happen anyway and this way, Germany would have a limitation. (21) It also avoided the bother of collective security. (25) To conclude, there was no desire, born of fear, as there was in France, to keep Germany permanently weak and harmless. (25)

British Rearmament

The state of British defences was, in Baldwin’s own words, disquieting, and a greater British defence effort might indeed have seemed to be in order. (25) Yet, following upon Hitler’s rejection of both the League and the Disarmament Conference, Baldwin took exactly the opposite approach. (25) He continued a freeze in the production of military aircraft, which had been instituted in 1932. (25) The gesture was intended “as a further earnest of His Majesty’s Government’s desire to promote the work of the Disarmament Conference.”

German-Polish Pact 28th January 1934

In 1934 (15,20) Hitler signed a nonaggression pact with Poland, (2,15) by which the two countries promised not to attack each other for 10 years. (15,20) It was the first of his infamous ten year non-aggression pacts. (20) This caused a surprise in Europe at the time. (20) The alliance broke Germany’s diplomatic isolation while also weakening France’s series of anti-German alliances in Eastern Europe. (20) For the next five years Poland and Germany were to enjoy cordial relations. (20) However like many of his agreements, this was a tactical move. (20) Hitler wanted the Danzig Corridor because it divided the country in two and was inhabited by German speaking people (21) and he had no intention of honouring the agreement in the long term. (20)

Austria 1: 25th July 1934

Hitler himself was Austrian and Austria contained 8 million German speaking people. (21) Joining it with Germany (‘Anschluss’) was banned by treaty of Versailles. (21) In July 1934 an attempt by Austrian Nazis to overthrow the government in their country was crushed. (20) The Austrian Prime Minister Dollfuss was killed in the attempt. (20) Hitler at first supported the attempted coup but disowned the action when it was clear it would fail. (20) Italy reacted with great hostility to the prospect of Austria falling into Nazi hands and rushed troops to the border with Austria. (20)

Saar January 1935

Hitler started to undo part of the Treaty of Versailles in a slow and clever way. (15) At first he did things he was allowed to and this included returning the Saar back to Germany. (15) The Saar (2,4) [OR] Saargebiet (6) was an industrial area (15,21) with iron (21) and a coalfield. (16,21) It had been taken away from Germany in the Treaty of Versailles (10,16) to reduce the industrial capabilities of Germany. (10) It was important to regain it for the German economy. (21) It was put under the control of the League of Nations (15,20) and had been administered by the French since 1919. (6,15) This allowed the French to exploit its coalfields for 15 years. (20) It was included in the French economic sphere (using the Franc as its currency). (6) A Plebiscite (vote) or referendum was to be held after 15 years: (15) [OR] In 1935 the people of the Saar were allowed a plebiscite (16) to decide if they wanted to return to Germany. (15,16) The Nazis launched a propaganda campaign (15,21) to convince Saarlanders to vote to be reunited with Germany. (15) In January (16) 1935 (4,6) the population of the area voted to rejoin Germany (2,6) by an overwhelming majority, (6,16) of 90% (15,21) [OR] over 90 %. (16,20) The Nazis celebrated and claimed this was the start of removing the Treaty of Versailles piece by piece. (15,16) The decision was a big step forward for Hitler (15,20) in his campaign to reunite all German-speaking people. (21) The Plebiscite result was a major propaganda boost enabling Hitler to claim that his policies had the backing of the German people. (20) It gave Hitler the courage do admit to conscription. (21)

Repudiation of Versailles March 1935

In March 1935, Hitler (7,17) unilaterally (7) rejected the Versailles Treaty (4,17) and cancelled its military clauses. (7,17) believing that the western powers would not intercede. (19) His actions brought immediate condemnation from France and Great Britain, but (19) When they did nothing (10) [OR] took no military action (19) in reaction to this, Hitler was emboldened to reoccupy the Rhineland and reunify Germany. (10) [OR] figured that if he changed his efforts to the eastern areas of Europe, then France might be less willing to get involved militarily. (19)

The Stresa Front, April 1935

Britain, Italy and France formed the Stresa front (20) to reaffirm the Locarno Treaty (25) and protest at German rearmament (20) and conscription. (21) They guaranteed to protect Austrian independence. (21) but took no further measures (20) against rearmament. (21) Britain did not want to spend on armed forces. (21) French did not stop because instead they put their money in building forts to defend from Germany Maginot Line. (21) Italy was closest to taking action. (21) Mussolini would not allow Anschluss, and placed his men in threatening positions to warn Germans. (21) This united front against Germany was further weakened when Italy invaded Ethiopia. (20) Even after the Stresa Front reaffirmed the “spirit of Locarno,” Hitler would not stop any of his pursuits, and became more confident. (25)

Russo-French Pact May 1935

In May (10,22) 1935, France and the USSR signed a treaty of friendship and mutual support. (10,17) Hitler resented this and argued that it was a hostile move against Germany: (10,17) he said it was a violation of the Locarno Pact. (19) He used this as an excuse to send German troops into the Rhineland in March 1936, contrary to the terms of the treaties of Versailles and Locarno. (22) The Chimaera of a coalition between the French and the Soviet Union that would threaten British security intimidated the Foreign Office into the misjudgment. (25) By 1936, Laval sought rapprochement with Germany, relied heavily on cooperation with Fascist Italy, and dealt in personal diplomacy. (12)

Abyssinia 3rd October 1935

The same year Italy invaded Ethiopia. (6,20) the League of Nations called upon her members to boycott Italy economically. (6) France, Italy’s foremost trading partner, joined the boycott (6) [OR] appeased Italy on the Ethiopia question because it could not afford to risk an alliance between Italy and Germany. (12) Hitler ignored international protests and supported Mussolini. (20) This ended Germany’s international isolation and the Italians signalled their acceptance of German influence in Austria and the eventual remilitarisation of the Rhineland. (20)

The Rhineland invaded

Status Quo

The Rhineland had been part of France during the Napoleonic wars (late 1790s). (17) It became part of the German state of Prussia in 1815. (17) Under the terms of the Versailles settlement (11,15) and the Locarno Pact (7,23) Germany had political control over the area (17) but was not allowed (11,13) to erect fortifications (20) or have troops (11,13) forces in a 50 km stretch of (16) the Rhineland, (11,13) a strip of German land (10,15) that lies along (17,20) the right bank of (20) the Rhine River, (17,20) bordering France, Belgium, the Netherlands (10,17) and Luxembourg, (17) German troops stationed there would be too close to France’s borders. (11,23) and excluding them was to increase the security of France, Belgium, and the Netherlands against future German aggression, (10) It is a key industrial region (16) producing coal, steel (11,16) and iron. (10) It is rich in mineral resources. (17) The location of the Rhineland contributed to the growth of the Ruhr coal-mining district. (17) The Re-occupation of the Rhineland would probably lead to the Germans constructing defences which would make French pledges to Eastern European nations harder to fulfil should the need arise. (23) Demilitarizing was regarded as an insult to German self-respect. (21) It bordered France, (11,13) and in the event of a war, the River Rhine, if properly defended, would be a difficult obstacle for an invading force to cross; not defending it, Hitler said, made Germany vulnerable to invasion (16) as it could be used by France to invade Germany (10,17) via Belgium , Holland and France. (21) [OR] It DID leave Germany thus vulnerable. (21) Most people expected the Germans to send troops into the Rhineland. (20)

Planning

In March 1933, Werner von Bloomberg, Germany’s Defense Minister, had plans drafted for the remilitarization of the Rhineland. (19) Many of Germany’s leaders felt that remilitarization should only occur if it was diplomatically acceptable and firmly believed that it would not be possible to reinstate military force before 1937. (19) By January 1936, Hitler had made the decision to reoccupy and militarize the Rhineland. (19) He had originally planned to remilitarize this area in 1937, (19) but decided to change his plans to early 1936 because of the ratification of the 1935 Franco-Soviet pact. (10,19) Hitler also thought that France would have more military armed forces by 1937. (19) On February 12, 1936, Hitler told his Marshal Werner von Bloomberg (his Field Marshall), of his intentions. (19) He met with General Werner von Fritsch, to find out how much time would be needed to move several infantry battalions and one artillery battery to the Rhineland area. (19) Fritsch responded that it would most likely take at least three days to organize the plan. (19) He also told Hitler that Germany should negotiate the remilitarization of the Rhineland because he thought that Germany’s military forces were not ready for military action with French armed forces. (19) General Ludwig Beck (Hitler’s Chief of the General Staff) also cautioned Hitler that their military forces would not be able to successfully defend the country if France attacked them in the Rhineland. (19) Hitler told Fritsch that he would order all German armed forces out of the area if France intervened militarily. (19) The Rhineland remilitarization operation was given the code name Operation Winter Exercise. (19) It was a test to see how far France would go to secure the terms of the Treaty of Versailles. (17) He said “The forty-eight hours after the march into the Rhineland were the most nerve-racking in my life…. (20)

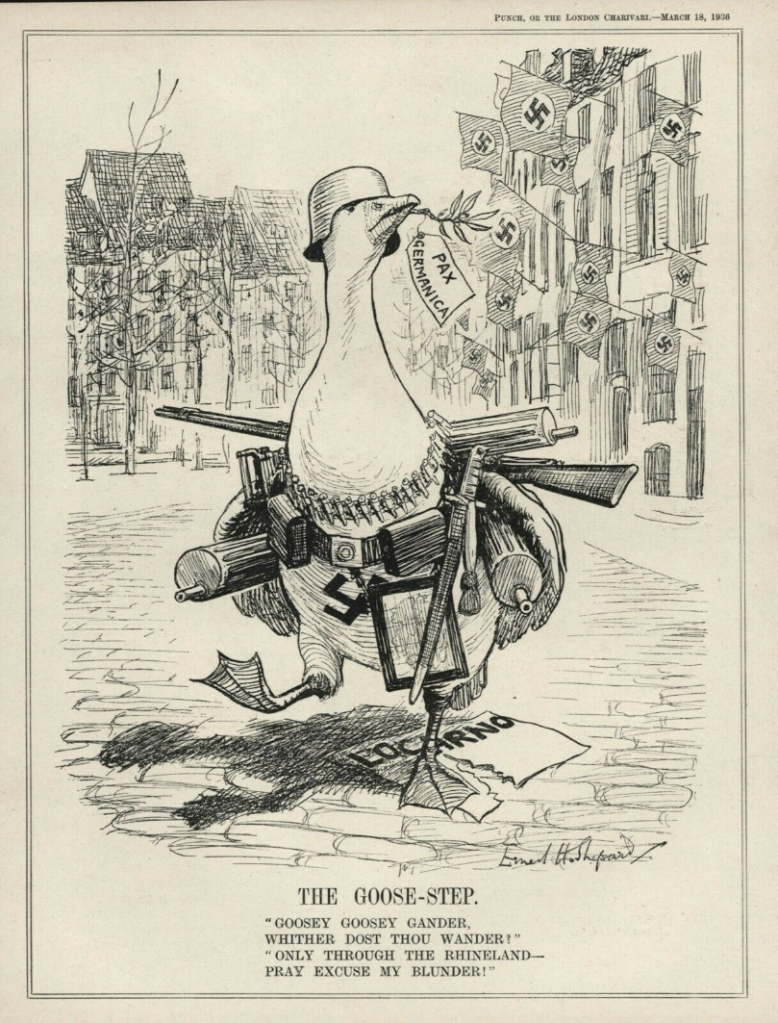

Operation Winter Exercise March 7th

Most people expected the Germans to send troops into the Rhineland, the question was when? (20) This question was answered when, shortly after daybreak (19) on March (7,10) 7th, (10,13) 1936, (7,10) Hitler, in one of his many Saturday surprises, (20) denounced the Locarno Pact (7,19) announced that his troops had entered the Rhineland. (20) He had remilitarized the Rhineland (2,4) by sending in a small force (20) of nearly twenty German infantry battalions, along with a small number of planes (19) more than 20,000 troops, (10,15) specifically 32,000. (15) [OR] about 32,000 armed policemen and soldiers. (19) They were significantly outnumbered by the French military force that was close to the border. (19) This was the first time that German armed forces had been in this area since the last part of World War I. (19) They were ordered to reoccupy the demilitarized zone which included Saarbrucken, Aachen, and Trier. (19) By 11:00 a.m., they had reached the Rhine River, after which three battalions crossed over to the Rhine’s west bank area. (19) Soon after, German reconnaissance forces discovered that several thousand French troops had congregated very close to the Franco-German border. (19) German re-armament had not yet reached a point where they felt ready to take on a well-armed nation like France. (22) At this point, General Bloomberg pleaded with Hitler to evacuate all of their armed German forces from the Rhineland territory. (19) Hitler then asked if the French military forces had in fact crossed the border area, and when he was told they had not, he informed Bloomberg that they should stay the course unless the French Army crossed the border. (19) It has been reported that even though Bloomberg was extremely nervous during the course of Operation Winter Exercise, (19) Baron Konstantin von Neurath (Hitler’s foreign minister) (2,19) remained calm and told Hitler not to withdraw the Germany Army. (19) Hitler commented that the Rhineland military operation was an extremely nerve-racking time for him. (19,20) “If the French had marched into the Rhineland, we would have had to withdraw (20,21) with our tails between our legs, for the military resources at our disposal would have been wholly inadequate for even moderate resistance.” (20) This move was (8a,10) therefore (11) the first (8a,10 [OR] one of the first (13) of many (8a,10) direct violations of the Treaty of Versailles by Adolf Hitler. (10) [OR] Germany had begun rearmament in 1935. (2,4)

Significance

The reoccupation and fortification of the Rhineland was the most significant turning point of the inter-wars. (17) The Treaty of Versailles and the Locarno treaties had been broken. (21) Hitler offered France and Britain a 25 year non-aggression pact and claimed ‘Germany had no territorial demands to make in Europe’. (16)

Responses to the German re-occupation

General

The occupation of the Rhineland, in terms of foreign relations, threw the European allies, especially France and Britain, into confusion. (22) The French viewed the de-militarised zone as a crucial part of their security. (23) It enabled them to easily occupy the Ruhr Valley in the case of probable German aggression and was, to them, one of the most important clauses of the Treaty of Versailles. (23) No nation wanted to risk another world war, and the Great Depression had reduced countries’ ability to afford war (11) but Britain and France could have stopped Hitler when he was too weak for war. (15) Hitler feared that Britain and France would try to stop him (15,17) and had ordered that troops should be withdrawn if France decided to attack or take action, (17) but again, like with the Saar region, (10) Great Britain and France, (8a,10) who were supposed to be the guardians of the Treaty of Versailles through the League, (8a) did nothing (8a,12) [OR] nothing substantial in reaction to (10) this breach of the treaty. (10,17) Neither Paris nor London would risk war, (12) No nation felt that they had sufficient money (8a,11) or troops to stop Hitler. (11) [OR] There was a lot of sympathy in Britain for the German action. (20) The British were therefore not prepared to take any action, and without British support the French would not act. (20) Versailles was dead. (14,17) Hitler had gambled and won. (20) The League of Nations also did nothing except condemn Hitler. (15) They were more concerned with Mussolini in Abyssinia. (15) Thus global collective security was threatened. (17) Britain and France chose instead to sign agreements expressly negating the terms of Versailles. (14) After March of 1936, they could no longer take forceful action against Hitler except by provoking the total war they feared. (17) There was, therefore, an escalation of tensions between Germany and other European countries. (17) Germany was rebuilding its army again and more armaments. (17) Nations feared that war would soon break out and so they began to try and appease Hitler. (17)

Specific to Britain

General attitudes to Germany

All the key issues relating to Appeasement are present in the Rhineland event. (22) Memories of the horrors and deaths of the World War (3,11) inclined many Britons (3,18) – and their leaders in all parties (3) – to pacifism in the interwar era. (3,18) Appeasement was popular : in the early 1930s people voted against war and in favour of collective security. (18) Britain was (and is) a democracy, and fighting a major war without broad support would have been foolish. (18) The Treasury had wanted to address high unemployment rather than pay for armaments, (18) so the armed forces were inadequate. (18,22) British people were also very anti-communist (20,22) believing that communism was an evil to be avoided an any cost; mistrust of our key allies; weakness of the League of Nations. (22) The British press concentrated on the repression by Stalin and the secretive system of the Soviet Union. (20,25) Although Germany after Hitler’s control had boosted up its armaments, the British administration responded with further disarmament, and Stanley Baldwin, then prime minister, regarding a possible German invasion, “did not consider such an attack likely”. (25) Some in Britain (11) [OR] ‘many’ (20) agreed that the Treaty of Versailles was too hard on Germany. (11,18) They were ready to revise it, (1822) and there was a lot of sympathy for the German actions: (18,20) Since the early 1920s many British politicians (18) [OR] People who thought like that were, in principle, willing to make adjustments in favour of Germany. (18) The affiliation of the British Government with the German became so close that the anti-Semitic movements and eugenic craze in Nazi Germany were, by official British authorities, treated as unfounded, exaggerated, or were simply ignored. (25) The same attitude was displayed by the American government to such reports. (Akshay book) Many Tories feared bolshevism, and stupid ones thought of Hitler as a sort of guarantee against future encroachments westward on the part of Russia. England and Germany should be allies against Russia, the great communist enemy. Moreover, Russia has always been a “traditional” foe; communism serves to make it doubly dangerous. (25) The city of London, with enormous investment in Germany, allowed itself to be dazzled by the spurious brilliance of Dr. Schacht. (25) A great many powerful persons in Britain hated France and the French, and therefore tended to be pro-German. (25) A group of personalities around Lord Lothian (formerly Philip Kerr, Lloyd George’s alter ego at the Peace Conference, and now British Ambassador to the United States), for a considerable time thought that a stable Germany, under Hitler, would insure peace. Lothian was a Christian Scientist and Christian Scientists, who do not believe in death or evil, found it easier than members of other religions to accept at face value Hitler’s promises. (25) The London Times (Lothian and Geoffrey Dawson, its editor, were close friends) was, of course, irrefragably independent; its Berlin correspondents had performed noble service in revealing Nazi brutality and prejudice; but it disliked the communists more than the Nazis, and sometimes it gave Hitler more than the benefit of the doubt in matters of foreign policy. (25) A tendency existed in England to be sorry for Germany in its role of conquered but honorable foe. (25) (By contrast, the French will never forgive Germany for the injustices of the Treaty of Versailles.) (25) Oddly enough, some forces in the Labour party were pro-German. It is obvious that British socialist and trade unionists under Nazism would suffer even as their German colleagues, but labour foreign policy in Great Britain was erected on dislike of the Versailles Treaty and plea for fair play to Germany, and even outrages performed upon labour by Hitler did not much modify pro-Germanism in some circles of the British Left.

“…the feeling in the House [of Commons] is terribly pro-German, which means afraid of war.”

H Nicholson, British MP. (23)

The Rhineland in particular

A study of the Rhineland crisis is an excellent case study of British appeasement policy. (22) The British leadership (19) did not think the Rhineland was a big problem. (11) They thought that in this particular case Nazi Germany was just ‘entering their own backyard’ (19,21) (Lord Lothian (23)) and that there was no need to enforce this part of the Treaty of Versailles. (19,21) The Foreign Office expressed frustration over Hitler’s unilateral move because they had been proposing a negotiation for Germany to remilitarize the Rhineland territory. (19) The Foreign Office complained that Hitler had deprived them of the possibility of a concession which could have been very useful to Great Britain. (19) It’s not clear how well informed Baldwin and Chamberlain really were about the intentions of the Nazi regime. (18) Some still assumed that Hitler was a reasonable politician with reasonable demands and should be dealt with as such. (18,22 The Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs was Anthony Eden, the Prime Minister was Stanley Baldwin. (22) He met with the French, Belgian and Italian governments. (22) Partly because of this, the British government decided to do nothing. (22) [OR] to propose talks with Hitler over the Rhineland region: something they had already proposed to hold in any case. (23)

After the fact

There was dismay at the fact that Hitler had chosen to act, in breach of Treaty requirements, but no desire to go to war over the issue. (23) Two days after the event , Foreign Secretary Eden issued a Policy Memoradum:

“We must discourage any military action by France against Germany. A possible course which might have its advocates would be for the Locarno signatories to call upon Germany to evacuate the Rhineland. It is difficult now to suppose that Herr Hitler could agree to such a demand, and it certainly should not be made unless the Powers, who made it, were prepared to enforce it by military action. Fortunately, M. Flandin [French Foreign Minister]has said that France will not act alone but will take the matter to the Council [of the League of Nations]. This he must be encouraged to do. But we must beware lest the French public, if further irritated or frightened, get restless at such a slow and indecisive action and demand retaliatory action of a military character such, for instance, as the reoccupation of the Saar [German territory ceded to France by the Treaty of Versailles and returned to Germany in 1935]. Such a development must be avoided if possible. While we obviously cannot object to the Council adopting … a ‘finding’ that Germany has violated the demilitarized zone provisions, this ought to be on the distinct understanding that it is not to be followed by a French attack on Germany and a request for our armed assistance under that article … We must be ready at the Council to offer the French some satisfaction in return for their acquiescence in this tearing up of articles 42 and 43 of Versailles [i.e. demilitarization of the Rhineland] and of the whole of Locarno … In the face of this fresh and gross insult to the sanctity of treaties, it will be difficult to persuade the French to sign any fresh agreement with Germany in present circumstances … We might agree to [M. Flandin’s suggestion of a formal condemnation by the Council of Germany’s action], but we ought to resist [measures that could include economic and financial boycott] … The essential thing will be to induce or cajole France to accept [negotiations with Germany]. The trouble is that we are in a bad position to browbeat her into what we think reasonableness, because, if she wishes to do so, she can always hold us to our Locarno obligations and call upon us to join with her in turning the German forces out of the Rhineland. The strength of our position lies in the fact that France is not in the mood for a military adventure of this sort.” (23)

Following the discussions described in the documents, the British Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, did indeed meet the German ambassador and make his proposals. (22) which were to netotiate with the Germans over the size of any force which could be deployed in the Rhineland. (23) Hitler refused to withdraw his troops, and put pressure on the League of Nations to act. (22)

Specific to France

French general policies

A few minutes with a good atlas of Europe should make it clear that Britain would have had to act *through France*. (18) In the 1920s France had continued her (6,9) military (9) alliances with Eastern European countries (6,9) (Poland, Czechoslovakia, Rumania and Yugoslavia) (6) countries which were too weak to help it. (9) Its weakness (8a,9) had been compounded by the Great Depression that plagued the 1930s. (9,11) By that time France became a deeply conservative, defensive society, split by social conflict, undermined by failing and un-modernized economy and an empire in crisis. (12) All these things explain the loss of will and direction in the 1930s. (12) In the mid and late 1930s France was bitterly divided into Left and Right and not well placed to take decisive action, (18,21) as the events of 1940 made very clear. (18)

French Foreign Policy: Laval 1934-6

The foreign policy of right-wing Prime Minister Pierre Laval (1934–1936) was based on a distrust of Britain. (12) Appeasement was increasingly adopted as Germany grew stronger, for (12) France was increasingly weakened (8a,12) by a stagnant economy, (11,12) unrest in its colonies, (8a,12) and bitter internal political fighting. (12) Martin Thomas says it was not a coherent diplomatic strategy nor a copying of the British. (12) French military strategy was entirely defensive, and it had no intention whatever of invading Germany if war broke out. (12) Even worse, on February 3, 1935, the French and British Government issued a communique recognizing Germany’s right to rearm, but not without consulting the other Powers, and asking for a direct exchange of views. (25) in May (10) 1935, (10,12) Laval’s government made a political alliance (9,10) [OR] defence agreement (12) with the Soviet Union (10,12) signed by Laval in (12) but it dared not cooperate militarily with the USSR, (9) so the agreement was not implemented by him or by his left-wing successors. (12) France was strategically dependent on Great Britain, which flatly refused to consider any military commitment: (9) [OR] Great Britain’s leaders had consented to talks with France about remilitarization negotiations. (19) The only figure that seemed to grasp the danger of this kind of thinking was Winston Churchill. (25) He said: (25)

“The awful danger of our present foreign policy is that we go on perpetually asking the French to weaken themselves. And what do we say is the inducement? We say, weaken yourselves, and we always hold out the hope that if they do it and get into trouble, we will then in some way or other go to their aid, although we have nothing with which to go to their aid. I cannot imagine a more dangerous policy. There is something to be said for isolation; there is something to be said for alliances. But there is nothing to be said for weakening the Power on the Continent with whom you would be in alliance, and then involving yourself more [deeply] in Continental tangles in order to make it up to them.”

Without the deterrence of a united Anglo-French resistance, France was militarily helpless (12) and did not want to risk war. (21) [OR] French forces in the area were much bigger and Germans had ordered that troops should be withdrawn if France decided to attack or take action, (17,19) Several British ministers were unsatisfied with the direction of the negotiation talks. (19) This arrangement was a prescription for a nervous breakdown, not a grand strategy, says Kissinger. (9) British historian Richard Overy says that the country that had dominated Europe for three centuries wanted one last extension of power, but failed in its resolve. (12)

After the Event

France was angered by the occupation of the Rhineland but (13) without a viable strategy (13) France could not respond. (12,13) France was on the verge of a general election (22) and would not act without Britain’s support. (13,22) Eden was right to say that ‘France is not in the mood for a military adventure of this sort’. (23) Britain did not fully denounce the move. (13) France’s failure to send even a single unit into Rhineland signalled that strategy to all of Europe. (12) Four days after the incursion, the French Foreign Minister said:

“…what has been violated is a treaty into which Germany freely entered. (23) It is a violation of a territorial character, a violation following upon repeated assurances by the German Chancellor [Hitler] that he would respect the Locarno Treaty and the demilitarized zone on condition that the other parties did the same. (23) It was a violation committed in the very middle of negotiations … If such violations are tolerated by members of the League as a whole, and in particular by the Locarno Powers, there is no basis for the establishment of international order, and no chance for the organization of peace through a system of collective security under the Covenant (of the League of Nations). France will therefore ask the Council of the League to declare that there has been a breach of articles 42 and 43 of the Treaty of Versailles [decreeing demilitarization of the Rhineland] As to the fact of this breach, there can be no possibility of doubt. Once the breach has been declared by the Council, the French Government will put at the disposal of the Council all their moral and material resources (including military, naval and air forces) in order to repress what they regard as an attempt upon international peace. The French Government expects that the Locarno Powers, in virtue of their formal obligations, will render assistance, and the other members of the League … will act with the French Government in exercising pressure upon the author of this action. (23) The French Government does not by this mean to indicate that they will refuse in the future to pursue negotiations with Germany on questions interesting Germany and the Locarno Powers; but that such negotiations will only be possible when international law has been re-established in its full value…” M Flandin, March 10th, 1936. (23)

Coming up with such tempting bargains such as a non-aggression treaty with France and claiming to have technically occupied its own territory, Nazi Germany tormented the Allies with doubt of whether Hitler was actually up for peace. (9) While the Allies were troubling themselves in the fatal bewilderment, France acceded to (9) the constant British call for appeasing Germany, (9,24) and thus the French lost their ultimate defence line against Germany. (9) French credibility in standing against German expansion or aggression was left in doubt. (12) because Germany could now protect the Ruhr with troops situated on the border with France. (21) Potential allies in Eastern Europe could no longer trust in an alliance with a France that could not be trusted to deter Germany through threat of an invasion. (12) The ‘little entente’ was weakened. (21) Belgium dropped its defensive alliance with France and relied on neutrality. (12)

Specific to Germany

By the 1930s Hitler had seized the initiative from Britain. (18) [OR] Hitler’s remilitarization of the Rhineland changed the balance of power decisively in favour of the Reich. (12) Germany was able to build a line of forts there (known as the ‘West Wall’), so if Hitler broke treaty of Versailles again, no military action could go against them. (21) It stirred up the nationalistic feelings of the German people, (17) assisting him in his aim to win over the German people through education, censorship and propaganda. (21) His foreign policy successes in the 1930s were to make him a very popular figure in Germany. (20) As one German political opponent described: “Everybody thought that there was some justification in Hitler’s demands. (20) All Germans hated Versailles. (20) Hitler tore up this hateful treaty and forced France to its knees…. (20) people said, “he’s got courage to take risks”. (20) It secured Hitler’s popularity with not only his army generals, (19) but also with the German people. (15,17) who were pleased (15,17) by the lack of a response by both Britain and France, and the evidence that he would not be challenged as he expanded his aggression; (13,17) it encouraged Hitler to continue to go against the treaty and pursue his Foreign Policy aims. (15,17) Hitler moved on from the occupation of the Rhineland in 1936, to the annexation of Austria and the seizure of the Sudetenland in 1938, to the take-over of the rest of Czechoslovakia in March 1939 and then Poland in September 1939. (22) We know that those men sitting round the Cabinet table in Downing Street in March 1936 had no idea that they were only three and a half years away from war. (22) We must not judge them with hindsight. (22) Appeasement is an important phase in British foreign policy; it helps to explain why the Second World War broke out when and how it did. (22) It also traumatised a generation of British politicians into trying to redeem themselves, from Suez in 1956 to the Falklands in 1982. (22) The extracts from the Cabinet minutes show how little room for manoeuvre British politicians actually had. (22) It was going to be re-played again over Czechoslovakia in 1938. (22)

After the Re-occupation

The rise of fascism had provoked a coming together of centre and left groups in ‘Popular Fronts’, as a result of which Communist Russia was admitted to the League. (8a) The election victory of the Popular Front in France in May, 1936 served as a major irritation in Europe’s political landscape, as Britain, for a brief moment, toyed with the idea of an Anglo-German-Italian alliance versus the communist powers (USSR and France). (6) Following the remilitarization of the Rhineland, Hitler spoke in public about his wish to have peace throughout all of Europe. (19) He even wanted to engage in talks with France and Belgium about agreeing to new non-aggression pacts. (19) While doing so, Germany was very rapidly constructing defensive fortifications along the Belgium and French borders. (19)

Spanish Civil War

Germany militarily assisted the supporters of Francisco Franco in the Spanish Civil War, (2,8a) starting in July (2) 1936. (2,8a) Mussolini also helped Franco, while Stalin helped his enemies. (8a) As with the Rhineland, Britain and France did nothing: neither trusted the other to cooperate. (8a) Both governments were sympathetic to Franco, but both had populations who were pacifist or sympathetic to communism. (8a) Both were militarily weak and feared the cost of a new war. (8a)

Appeasement 1937-9

Britain and France did not want to enter into a military conflict with Germany at this time as both had been reducing their armies and ability to wage war. (13) This lack of will to fight pushed (13) both countries towards the policy of appeasement. (5,13) [OR] France prepared herself for another war. (6,20) The main element of that preparation was the Maginot Line, (6,12) a chain of fortresses along the Franco-German border – France believed it to be impregnable. (6,20) This was an entirely defensive strategy. (12) The British government, headed largely by Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, (5,13) appeased (1,3) Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany in the 1930s. (1) Chamberlain had become Prime Minister in May 1937 and inherited a very difficult situation. (18) Neville Chamberlain proposed it as the best means of containing Nazi aggression and avoiding a world war. (13) When opponents tried to appease him, Hitler accepted the gains that were offered, then went to the next target. (4) Hitler took advantage of Chamberlain’s naivety from the remilitarization of the Rhineland up to the Munich Conference. (18) Historians say that Chamberlain appeased Hitler in order to avoid war, others say that he was propelling Europe into war by basically allowing Hitler to do as he pleased. (18) Britain never had much influence in Eastern Central Europe. (18) It was an area where Britain could only have acted by proxy. (18) There’s a widespread belief that all Britain needed was to “do something”, but very few are realistic about what that something should have been. (18) A thunderous roar of condemnation (for example, in 1935 or 1936) might well have strengthened, not weakened Hitler, as Germans would have rallied round. (18)

Austria, Czechoslovakia and Poland

Due in part to the lack of reaction to the reoccupation of the Rhineland, (10) Hitler began to take over other lands throughout Western Europe. (8,10) Two years after the reoccupation of the Rhineland, Nazi Germany burst out of its territories, absorbing Austria and portions of Czechoslovakia. (8) At the time, all the concessions made towards Adolf Hitler and his government, such as allowing the annexation of Austria and Czechoslovakia, were believed to be positive moves by the British politicians and the general public. (5) After the British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain finalized the Munich Agreement, a wide-scale anti-appeasement campaign began, which included several prominent members of the British public. (5) As Hitler prepared for invasion of Poland, Chamberlain had no choice but to issue an ultimatum to Hitler over Poland – invade Poland and risk war with Britain or step back from Poland and reintroduce peace? (18) In 1939, Hitler invaded Poland, leading to the outbreak of World War II in Europe. (8,18) Britain and an even more reluctant France declared war on Germany supposedly in order to uphold Polish sovereignty – but did absolutely nothing to give any practical assistance to Poland. (18) Appeasement continued well into WWII. (18) Among some British grandees there was talk of making peace – until the Nazis bombed civilian areas of London in September 1940. (18)

Was Appeasement reprehensible?

Had Britain and France resisted German aggression world war II might not have broken out. (18) The policy of appeasement is often considered to be one of the main causes of World War II. (13) A book named ‘Guilty Men’ was published by a few anonymous journalists, who accused pro-appeasement politicians of deliberately surrendering to the open bullying of Adolf Hitler, and called for their immediate removal from office. (5) They let Hitler rebuild the German army and navy, occupy the Sudetenland and Czechoslovakia. (18) Chamberlain persisted with appeasement well after the Czech Crisis, whilst stepping up rearmament to give him more time. (18) Hitler did not think that Britain would go through with its ‘ultimatum’ so invaded Poland sept 1939. (18) Viewed coldly, the declaration of war in 1939 bears the hallmarks of grandstanding, of an empty gesture. (18) In many ways it was a barely rational act. (18) If they had put up a fight at the beginning, perhaps Hitler would not have kept pushing until the situation turned into a World War. (18) Or maybe not. (18) Although Britain had a vast empire at the time it was rather weak in Europe. (18) As for Chamberlain being ‘naive’, people seem to think that politicians operate in a vacuum, which is not the case. (18) Appeasement gave Germany and other Axis powers an opportunity to build strength before attacking the rest of Europe. (18) It also gave Britain more time, too. (18)

Unused source material

(finish it yourself!)

The British reply to Hitler’s program of aggression was a typical compromise; first, the British bought off competition at sea by the famous Anglo-German naval pact; second, the cabinet announced measures to triple the British Air Force, and the great rearmament program got-slowly-under way. (25) The sympathy for Germany in England produced a certain paradox. (25) It was that they were pro-German and (many of them) anti-Fascist at the same time, which was tantamount to eating an orange, say with one half of the mouth, and spitting it out at the same time with the other half. (25) In policy it was that Britain was rearming against Germany, the only conceivable enemy, while a powerful share of opinion did what it could to strengthen the putative enemy’s mind. (25) Britain was, of course, waiting, playing for time, until its own tremendous rearmament plans should be complete. (25) On factor a), Russia, under the Bolshevik regime, was beginning to evolve some order out of the chaos of the war and so long as she would let other nations go their own way, the bulk of British opinion wished her well. (25) However, the Labour Government went rather further than most people approved in making a commercial treaty that also provided, under not very clearly defined conditions, for a loan. (25) This was in any case one of the issues of the election of 1924 (though the voters were at first chiefly concerned with their own social problems); it became the dominant one after the publication of the Zinovieff letter. (25) The Russian Government, while anxious for the overthrow of all capitalist administrations, was in no way averse to borrowing their money. (25) The labour administration disclaimed all connection with the third international (Comintern), but the opinion of the public was still suspicious and the incumbent government was heavily defeated in the next election. (25) The Conservatives came into power with Stanley Baldwin as premier and Austen Chamberlain at the foreign office. (25) The treaty was of course dropped. (25) Similar to the relations with the United States, domestic politics in Great Britain tended to become more and more isolationist. (25) If Britain were to join hands with the Soviet Union, Hitler would have found less and less leeway in his aggression against the Eastern province, or, for that matter, the Polish Corridor. (25) On the contrary, British foreign policy from 1930 onwards was focused on a highly conservative stance. (25) Quite a number of speculations can be made on the cause of such anti-socialist stance of the government. (25) Still adhering to their traditional policy of balance of powers, Britain traditionally gave a hand to the seemingly weaker coalition in the continent. (25) The judgment of the power dynamics within the continent, nonetheless, seems to have been utterly mistaken when it came to the post war decades following the First World War. (25) There indeed are a myriad of reasons and speculations that might try to explain the matter, yet the most concrete and principal explanation lies on the macroscopic power balance the British perceived in the 1920s and 1930s. (25) That is, the capitalist forces versus the Socialist and Communist coalition. (25) This might have been based on the belief that a Socialist coalition might overcome the capitalist forces in Europe. (25)